Why are gaming communities so terrible?

Published:

Now here’s a take.

I.

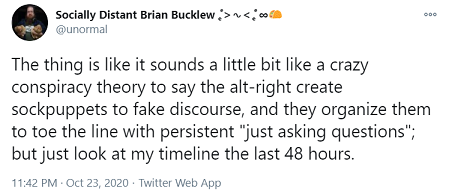

This post has largely been inspired by the following tweet:

I’ll just flat out say it: It’s definitely not a conspiracy. For those of you who aren’t in the know, I’ll summarize that the above tweet is referring to. Brian Bucklew is a game developer for Caves of Qud (CoQ), a “roguelike” game that is in “Early Access” on Steam. This essentially just means that players can buy and play an unfinished build of the game before its official release date. Anyway, the game has pretty good reviews and recently attracted attention since this guy posted a Youtube review of the game. I haven’t seen this Youtuber’s channel before, but seeing as their most recent videos have 1M+ views, I guess they’re pretty popular. During the video, the reviewer mentions that he got banned from CoQ’s official Discord server (if you’re not familiar, it’s basically Slack for gamers) and I guess that was enough to make his fanbase go ballistic, start a bunch of sock-puppet accounts, and start brigading Brian’s Twitter, CoQ game reviews on Steam, and the /r/CavesofQud subreddit.

So, what exactly are they so riled up about?

Basically, that they can’t dominate the CoQ Discord the way they want to. They will tell you that it’s because Brian is a dick who bans people for asking for a quest to play as the (racist) Templar (with a eugenics agenda) in CoQ, or that they’re paying customers and this is about free speech, or that they’re “just asking questions and trying to talk about the game”, but as Brian points out in his Twitter thread, this is claim is simply a red herring. They’re mad because Brian won’t let them do what they’ve done to every single other gaming space: dominate it, control it, then turn it into a safe space for “ironic” racist memes. In other words, they want to turn yet another Discord channel into yet another Nazi bar:

II.

If you go onto spaces like Reddit, and ask “Why are so many young alt-righters also gamers?”, the answer you will probably get is that the alt-right is a counter culture, that gamers are alienated from society and thus naturally fall into extremist groups, or that it’s all gamergate’s fault, and so on. I think these explanations all have a bit of merit – after all, human behaviour is really hard to pin down to a single “cause” – but I think what these answers miss is the possibility that there is something fundamentally baked into the philosophy of gaming itself. What the previous answers implicitly assume is that there is nothing wrong with video games and how they’re made, marketed, and consumed, there is only something wrong with who consumes them. If you’re playing a game, then that game is for you. The consumption of media is not random. This is becoming somewhat more obvious with the advent of algorithmic news feeds and Youtube recommender systems (try watching a couple Joe Rogan clips on Youtube, then see what happens to your feed, ugh) but I think this point often still gets missed. Media is explicitly, intentionally designed to feel as if it was consumed incidentally. You’re at your desk, trying to write a paper or something, open Twitter to take a break, and then suddenly 3 hours have gone by because you’ve been been watching Donald Trump and his supporters say stuff that is just positively, outrageously, insanely wrong. When you’re finally fed up and close Twitter, it’s time for dinner and you mentally kick yourself for having wasted so much precious time. Why are you even reading that stuff? You think Capitalism was a mistake, but somehow you keep “ending up” in these right wing spaces. It feels as if your encounter with those Twitter threads was incidental, but it wasn’t. It was the algorithm and the human brain working as intended. It’s called doom scrolling for a reason.

III.

Do video games push you towards fascist group-think? Even a little bit?

I’m not trying to construct an argument that will map to “video games are corrupting our youth” (I would be shooting myself in the foot), but I think that this is a fair question to ask if we accept the following premises: (1) The media we consume influences who we are and what we think, (2) the influences in (1) come in gradations, and (3) the consumption of media is not random.

I think assumptions (1) and (2) are actually true. Every piece of media we consume exerts its influence on us in some capacity. That is why advertisements can be aspirational but still work. It’s why advertisements work on us at all. It’s why after the movie Drive came out people started selling the jacket, it’s why the Proud Boys use memes as their “pen”, it’s why people cared about that WAP song with Cardi B, it’s why instagram seems to make us think we are ugly, it’s also why people binge The Office to feel better, and it’s why pointless sitcoms like to jam moral lessons into their content. The point here is that media exists precisely because it does influence us. It can make us feel good, or bad, affect our self-esteem, and affect our world views. I think it’s fine to accept this, with the understanding that the amount of influence each piece of media exerts varies from person to person. It’s probably hard to pinpoint exactly what that influence looks like in terms of worldview – you could probably hire a group of advertisement guys to figure it out – but, I’m willing to bet that influence is non-zero with a suitable choice of metric. So, let’s accept these premises: (1) media influences. And (2) by varying amounts.

What about (3)? I think the algorithmic news feed and its apparent effects on political discourse are sufficient evidence that (3) is true. If media consumption were actually random, then algorithmic news feeds wouldn’t work very well, since no real inferences can be made by observing a sample of someone’s browsing habits. So, I’m not sure how much time I should spend here. If you have a friend that tells you that there’s a movie you should see, do you (a) trust them and see the movie, (b) don’t see the movie because they have bad taste, or (c) you’ve already seen it/know you won’t like it. These decisions aren’t random, especially (c). People aren’t perfect uniform choice algorithms that select things to consume arbitrarily. They have tastes and preferences, which are potentially manufactured, and they make decisions based on that. Not random. It’s called doom scrolling for a reason.

So if we accept theses premises, what does that say about the video game? What does it say about the kinds of people who consume video games,and the kinds of video games people consume? If someone spends all their free time reposting Pepes for keks on a Discord server that’s for an obscure japanese role playing game (but actually it’s for racism), then the natural question to ask is: Why that video game?

(The Goblin Problem)

Feel free to skip this, or jump to the TLDR summary at the bottom. It’s going to get referenced going forward, so it should probably be mentioned and defined somewhere, but actually deciding where is hard. So, here it is. I don’t think this is the most original take – I might’ve internalized it from somewhere else – but it’s an important one, so I’m going to call it The Goblin Problem.

If you have ever played any kind of fantasy game that has knights, wizards, and non-human races (pretty much all of them), then your fantasy game will also have a basic enemy intended for the newbies and low level quests: goblins. The typical goblin enemy is small, green, with big point ears, a big nose and a love for getting the boys together and pillaging human(oid) settlements. A single goblin is usually fodder, practically irrelevant, but become dangerous when they attack en masse. The goblin is also almost always inherently evil. The only way to stop a goblin horde? Slay them all.

The interesting thing here is that goblins usually aren’t depicted as mindless animals (and even if they were…). They are usually depicted as being able to communicate, work together towards a common goal, and live in tribes. They often wear armor and can use somewhat complicated weapons like a sword and shield, or a long-bow. Sometimes, the goblins even have spell-casters or shamans – this means they can actually learn and internalize abstract concepts. In every single fantasy world, the use of magic and being able to use it boils down to (1) you understand that it is there, and (2) you can control it if you know “the secret”. Maybe the secret is reading enough scrolls, or tapping into latent powers, or whatever, but either way, it requires processing and understanding some kind of abstraction. Do you see where I am going with this?

Goblins are sentient. They are aware of themselves, what they are doing, and even why they are doing it, but that last point is never shared to the player, it’s never even discussed. Goblin bad. Goblin attck humans. Kill goblin. So far, this stuff is entirely consistent with the usual ingame world-building – I haven’t even tried to get political yet. The point here is that, even if it’s not discussed, goblins are a fully self-aware race of beings and they are always evil. They are always a scourge that needs to be wiped out. There is no reasoning with goblins, there is no cooperating, or treaties, or debates, there is only slaying.

This kind of world building is extremely common in fantasy games, and the insidious thing that is happening here is the subtext this kind of worldbuilding creates: there are entire races of beings that have no value, or worth, whose only purpose is to stomped on by people who are stronger/better/gooder the moment they cause problems. When playing these games, if it’s not explicit, then it is implicitly demanded that the player simply accept this as a fact. You cannot reason with goblins, it is simply impossible. Sure, maybe some games allow you to attempt a dialogue as a mechanic that is baked directly into the quest, and sure, maybe there is a way to resolve that conflict peacefully, but the general trope remains the same. Even in games that distinctly try to be progressive and have good politics by including LGBTQ characters and difficult morally-grey dialogue choices still contain long story sequences in which you have to go and genocide a camp of goblins. Maybe the game let’s you try to not genocide them, but if you fail a dialogue skill check, then welp. Better unsheathe your sword and tell your wizard to summon a fiery meteor, because they don’t call DnD characters “murder-hobos” for no reason.

Let’s summarize all this. The Goblin Problem occurs when a race of sentient, intelligent, communication-capable beings are taken to be explicitly, or implicitly pure evil, and no serious (long term) options exist for dealing with them, other than war, oppression, or genocide.

IV.

The problem with The Goblin Problem is that in a normal person who is anti-genocide, the very premise of the Goblin Problem is hard to accept. Really? The quest is to waltz into the Goblin King’s Kingdom and genocide them? That’s the only way to beat the game? Why is the only recourse for dealing with an intelligent race to simply stamp them out of existence? If it’s not outright distasteful, it probably should cause some level of immersion breaking. Now, I’m not about to say that if you blink a couple times and then kill the goblin anyway, you’re a bad person, but what is a bit more suspect is when you don’t even notice that you are accepting the premise that some races are just bad. In the context of a video game, they are probably fictional races, but here’s the thing: the video game was designed by real people with real beliefs. That’s why video games can be political at all, even if they’re taking place in a fictional universe. Final Fantasy 7 is a classic RPG, heralded as one of the best ever made. When you strip away the sci-fi, fantasy, and the weird stuff about aliens; what is it about? Eco-terrorists pushing back against the corporatized destruction of the world. Disco Elysium is even less subtle. It’s a fantastic, amazing game. Really. A total master piece in storytelling and world-building. And it’s distinctly relevant to the year 2020, since a major component of the narrative is the fact that centrist capitalists destroyed everything. Even if you step back and say “well, the game actually dumps on every political belief and system, it’s not really trying to push a political agenda”, I would probably rebut by saying that it was the centrist capitalists that destroyed everything.

Video games are made by people with real beliefs. Developers have worldviews and personal affects that get imprinted on everything they create. I don’t think that this can be helped. Maybe if someone is very careful about messages they’re sending out by writing a narrative in a certain way, then it could be avoided, but many video games center around a conflict. And conflict is something that arises through clashing forces. The root cause of that clashing, and the mode of resolution is the narrative, and that’s where the politics bleed in. Video game writers know that the narrative has to be justified, or else the player won’t buy into it, and get invested into it, and thus see no reason to continue. So if the narrative involves the slaughtering of countless sentient creatures, then that has to be justified too. Which is why the game will almost always give you an explanation. And that explanation is almost always just the Goblin Problem itself.

I want an example, and I’m not perfect, so here’s a conversation that actually happened when I tried to get a significant other to play Monster Hunter World with me.

Them: So, what’s the storyline to this game?

Me: It’s not too important. The main point of the game is hunting the monsters. The gameplay is really well designed. All the weapons are unique and –

Them: So we just go to this monster’s home and the kill it?

Me: Uh, yes. I mean, well, it’s more than – there is a story, it’s just not the main point –

Them: What if I don’t want to kill the monster? It’s just trying to live. Aren’t we the ones who are invading its territory?

I was sort of taken aback by this. Don’t they know that we have to fight the monster? But then I thought about it for a bit. I like to think that usually I’m pretty good at noticing the weird assumptions that I’m being asked to swallow whenever I read/watch/play something, but this caught me off guard. In hindsight, the reason I hadn’t noticed that I accepted the premise of the game is because I was enamored by how unique the gameplay was, how tight the controls were, and cool the weapons were, and because the game offered a justification for its premise like 5 minutes in: the monsters have actually gone rogue and since we are trying to put up a settlement in a new piece of territory called the New World, we couldn’t let them wreak havoc, and the only way to really deal with the monsters is by slaying the– Fuck, this is almost the Goblin Problem.

(I say “almost” the Goblin Problem, because the monsters are not sentient. They’re more like really big, dangerous animals, and in many of the quests there is an underlying cause that is making them go rogue. The rogue-ness needs to be dealt with, because the monsters can leave their habitat and then mess things up for the other monsters, but the way you solve the long term problem in the games is to find the root cause and stop that. The game also offers a “capturing” mechanic that means you actually don’t have to kill the monster – it’s implied that there is a catch-and-release thing going on. So it doesn’t quite fit. But the point here is that I missed this because I subconsciously just acknowledged that hunting “animals” that are “causing havoc” just makes sense.)

The problem with The Goblin Problem is that in many many examples of where it occurs, the Goblin Problem is both the problem and the answer. “Why do we have to kill the goblins? They’re sentient. Can’t you talk to them?” “No, you see, the goblins – they’re bad and talking won’t work so – You just have to kill them.” It’s just taken as a fact that, because you are the hero and because you are fighting the goblins, it’s the goblins who are the bad guys. This is related to the observation that some people make when they rewatch Star Wars as adults. When you see Star Wars as a kid, you think of you and your friends and your country as the good guys. That means you are The Rebels. But, when you learn a little about US foreign policy, you realize that actually, no, you and the rest of your country are The Empire. (Of course, I’m assuming that you’re American. Ugh! How American of me.)

Let’s take a step back. The issue here isn’t that there are games where the only answer is violence. Indeed, you could construct scenarios where the only answer is violence. The larger problem here is a kind of circular thinking: the conflict exists because violence is the only way to deal with the baddies, and the only way to resolve the conflict is to deal violence to the baddies. Even though we are talking about fictional races and wizards and things like that, this narrative device is political. That’s why you have to be aware of it. Because, if you’re not, then you will implicitly accept this reasoning, then use it to justify the story of the game. The baddies are bad, they have to be killed. The baddies are bad because we have to kill them.

Here is the very crucial point I want to make: If you are okay with this form of reasoning inside a video game, then that means you accept that form of argument.

Now, ask yourself. Who else uses that form of argument?

V.

I’ll just show you my hand and tell you what I’m trying to get at.

I’m not trying to say that any fantasy video game that suffers from chronic goblins is deserving of your ire, or that you need to feel bad when you play those games. I don’t really believe that all video games need to have good politics to be good games, or be fit for consumption. I also don’t think that you cannot or should not roleplay a Lawful Evil Undead Lich who keeps their friend’s soul on a desk in a crypt on a Friday night. But, I do think that even seemingly innocuous world building can, in subtle ways, push people towards accepting a kind of pattern for rationalization. A persistent problem that you will observe if you go to any right-winging space is the air of “us against them”. This mentality is really common in alt-right group think: it manifests into ranting about the media having a liberal bias in the best case, or to manic ravings about “white genocide” in the worst case. This mentality is also frequently used as a narrative device and justification for that narrative in video games.

If we accept that the media we consume influences us, even in small ways, then I think it’s fair to say that some video games can and do influence people into being more receptive to the kinds of arguments that come from the Alt-Right. If you accept The Goblin Problem in both premise and justification for that premise, then that same argument might work when trying to convince you that maybe it’s the brown people who are the problem. In this light, gamers being consistently problematic people makes sense, since they their consumption of video games might make them specifically vulnerable to the kinds of rationale that the Alt-Right makes. Once you start to make those same rationalizations for your behaviour, or your friends’ behaviour then you are the Alt-Right.

And the Alt-Right have an agenda that involves controlling spaces where discourse about things happen. Any discourse. Even about little games like Caves of Qud.

Post.

“So, what if I really like fantasy roleplaying games and fighting goblins?”

Go for it. No one is going to stop you. If you think my arguments are convincing, then probably what I would say is this: Just try to be a little bit critical of the narrative devices in your game. See if you can notice the assumptions the game is asking you to make. If have difficulty with this, then either the writing staff is really good at their job, or you’ve already bought in.

If you’re not sure what I mean, then here’s an example. Many of us in my generation grew up playing Pokemon. But at some point, most of us realized that capturing little animals and forcing them to fight each other was kind of… wrong. At least weird. When this realization hits, most people just kind of go “Huh.” Then go back to playing. The game is different now. You are aware of the device used in the game, so now you must actively suspend your disbelief.

If you can take a step back and turn a critical eye towards things you already enjoy, then that’s probably enough. Any amount of introspection over a choice of hobbies is probably better than zero introspection at all.